Oral tumors in dogs and cats are among the most commonly occurring cancers encountered in our patients. The most common location for oral melanoma is the gum (gingiva) or the buccal mucosa (inside of the cheek), but other locations have been reported such as the inner lining of the lips, palate, and tongue. Oral melanomas are locally aggressive and also have a high likelihood (80%) of metastasis (spread) to other organs such as the regional lymph nodes and lungs. Although most oral melanomas are very aggressive, there may be a small subset of these tumors, possibly including lingual (tongue) melanomas that may be less metastatic.

Symptoms of Oral Melanoma

Most cats and dogs with oral cancer have a mass in the mouth noticed by the owner. Pets with oral tumors will typically have symptoms of increased salivation (drooling), facial swelling, bleeding from the mouth, weight loss, foul breath, oral discharge, difficulty swallowing, or pain when opening the mouth. Loose teeth could be indicative of bone destruction due to the tumor.

Diagnosis

A thorough diagnostic evaluation of oral tumors is critical due to the variety of different tumors that could be present. Sedation or anesthesia is often required in order to examine the pet’s mouth, especially if the suspected tumors are located in the back of the mouth or involve the tongue. If the tumor is suspected to be malignant, chest X-rays can be done prior to biopsy to check for metastasis (spread) to the lungs. Bone destruction is not typically seen on X-rays of the jaw until greater than 40% of the bone is destroyed so what appears to be a normal X-ray cannot exclude the tumor’s bone invasion. Advanced imaging such as CT (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can be valuable tools in staging the disease (determining how advanced it is), especially for evaluating bone invasion and the potential extension of the tumor into the nasal cavity, pharynx, or the eye. The use of CT may eliminate the need for regular X-rays but CT/MRI imaging is more expensive.

Regional lymph nodes should be carefully assessed for any abnormalities, although lymph node size is not an accurate predictor of metastasis. In a study of 100 dogs, 40% showed normal-sized lymph nodes despite being positive for cancer cells, and 49% of dogs who showed lymph node enlargement did not actually have lymph node metastasis. Lymph node aspirates (isolation of cells for microscopic analysis to check for the presence of any cancer cells) are recommended for pets with oral cancers.

The final diagnostic step, which is done under anesthesia, is incisional biopsy. Biopsy is preferred over cytology to definitively differentiate between benign (noncancerous) and malignant (cancerous) tumors and determine the exact type of tumor present.

Treatment Options

Surgery

Surgical removal of oral melanoma is always the primary method of treatment whenever possible. Since many oral melanomas invade the bone, the surgery will aim to remove not only the tumor itself but also any associated boney structures. For oral melanomas, aggressive surgery is usually recommended given the aggressive nature of these tumors. Cosmetic appearance is generally good after most upper or lower jaw surgeries but can be challenging when both sides have to be surgically treated. While surgery can reduce the risk of local recurrence (tumor coming back), unfortunately, most dogs will eventually succumb to the tumor’s spread to other organs without further treatment. In a published study of 37 dogs whose oral melanomas in the lower jaw were removed by partial mandibulectomies (a surgery where part of the lower jaw was removed), the median survival time was 9.9 months (range 1-36 months), and 21% of dogs were alive after one year. Twenty of the 37 dogs were euthanized due to recurrent or metastatic disease.

Types of Surgical Intervention

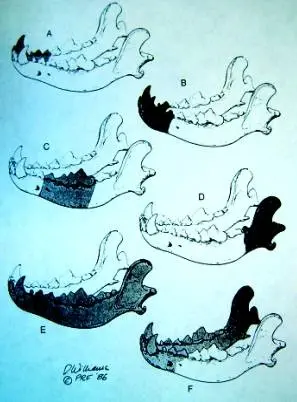

Mandibulectomy (lower jaw)

Classified according to the portion(s) excised

A. Unilateral rostral

B. Bilateral rostral

C. Central

D. Caudal

E. Total hemimandibulectomy

F. ¾ mandibulectomy

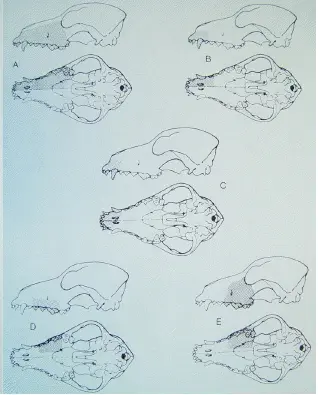

Maxillectomy (upper jaw)

A/B. Unilateral premaxillectomy

C. Bilateral premaxillectomy

D. Central

E. Caudal hemimaxillectomy

F. Caudal hemimaxillectomy

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is second to surgery in terms of the success of local tumor control. It is usually reserved for oral tumors that are unable to be removed completely. It is a well-tolerated form of therapy in animals.

Melanoma Vaccine

Malignant melanomas have a high metastatic rate (spread of cancer to other organs) in both human and veterinary medicine. For patients with malignant melanoma, the Oncept® Canine Melanoma Vaccine produced by Merial® has proven to be a successful innovation in extending remission up to three times longer than those previously achievable. This vaccine is administered into the inner thigh muscle of the dog with a needle-free transdermal device, and requires four initial injections at two-week intervals, followed by boosters every six months. The vaccine has an extremely low incidence of side effects.

The Canine Melanoma Vaccine treatment is new to veterinary oncology but has been fully approved. The vaccine works by alerting the patient’s own immune system to the presence of melanoma proteins. This is a novel approach in cancer medicine that results in the immune system fighting the cancer cells that remain in the body.

Prognosis

Oral melanoma is an aggressive disease with a high potential to metastasize to other organs, usually the lungs. The median survival of dogs with no treatment is 65 days. The median survival for dogs treated with surgery alone varies from 150 to 318 days with less than 35% of dogs surviving one-year post-diagnosis. The median survival time for dogs treated with radiation therapy is 211 to 363 days and for cats 66 to 224 days. Other factors such as the tumor size, stage, and success of the first treatment can also predict how well or poorly the pet will do. Dogs with tumors smaller than 2 cm diameter have a median survival time of 511 days compared to 164 days for those with tumors greater than 2 cm diameter or lymph node metastasis. This is in contrast to dogs with tumors bigger than 2 cm and metastases, who usually succumb to the disease within five months (approximately 25% of dogs will be alive one year after diagnosis if treated).

The addition of the melanoma vaccine to treatment protocols has been shown to significantly extend patient survival times. While the specific result varies from one patient to another, most patients experience a doubling or tripling of expected survival times.