Rolly is a 4-year-old SF Boston Terrier who presented to our Neurology service for progressive difficulty walking in her forelimbs.

Case Summary:

Rolly presented for a 2-month history of neck pain and weakness in her front left limb, which had significantly progressed over the past several days to her being unable to walk on her own. Oral gabapentin and meloxicam only minimally improved her signs at home.

Neurology examination:

- During her emergency neurology consultation, Rolly was unable to walk on her own due to significant left hemiparesis (worse in the left forelimb) and significant neck pain.

- She had decreased to absent proprioception in the left forelimb and both pelvic limbs.

- Her withdrawal and spinal reflexes (trigeminal and bicipital) in the left forelimb were significantly decreased.

- Her neurological examination was most consistent with a C6-T2 myelopathy (worse on the left) and she was admitted for an emergency cervical MRI due to the progressive and severe nature of her signs.

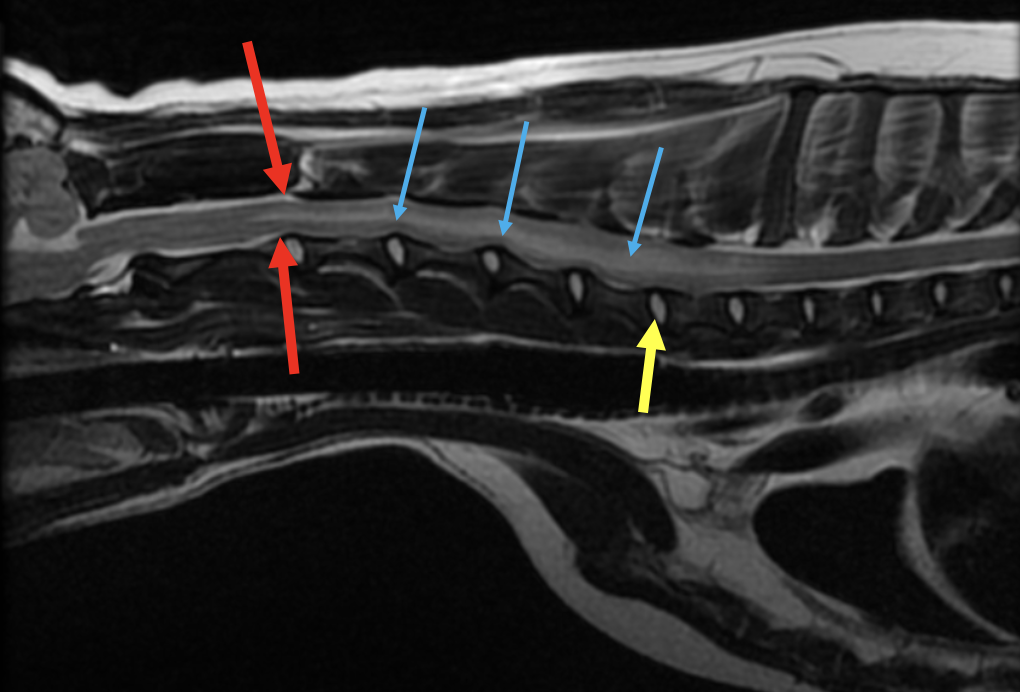

MRI findings (see Figure 1 below):

- Cervical MRI revealed a markedly hyperintense swelling associated with the spinal cord from C2 – T1 with loss of CSF patency but no extradural spinal cord compression. The intervertebral discs were all well-hydrated. There was severe contrast enhancement of the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord with suspected meningeal enhancement.

- This MRI finding is consistent with severe meningomyelitis (inflammation of the cervical spinal cord parenchyma and meninges).

Figure 1. T2 weighted sagittal (midline) view of the cervical spinal cord

The cervical spinal cord parenchyma is markedly hyperintense which is shown by the blue arrows. There is significant spinal cord swelling present, as there is loss of CSF signal (shown cranial to the spinal cord swelling by the red arrows). The yellow arrow shows a (normal) hydrated intervertebral disc.

Infectious CNS disease testing and a cisternal CSF tap were submitted due to the need to differentiate between an infectious cause (protozoal, tickborne, viral, fungal, etc), immune-mediated cause, and less likely neoplastic cause (lymphoma). She was sent home the next day on oral antibiotics that cover the most common causes of infectious CNS disease in Maine (clindamycin, doxycycline, and enrofloxacin) while her tests were pending. She was also given oral prednisone in case she neurologically worsened over the weekend despite antibiotic therapy.

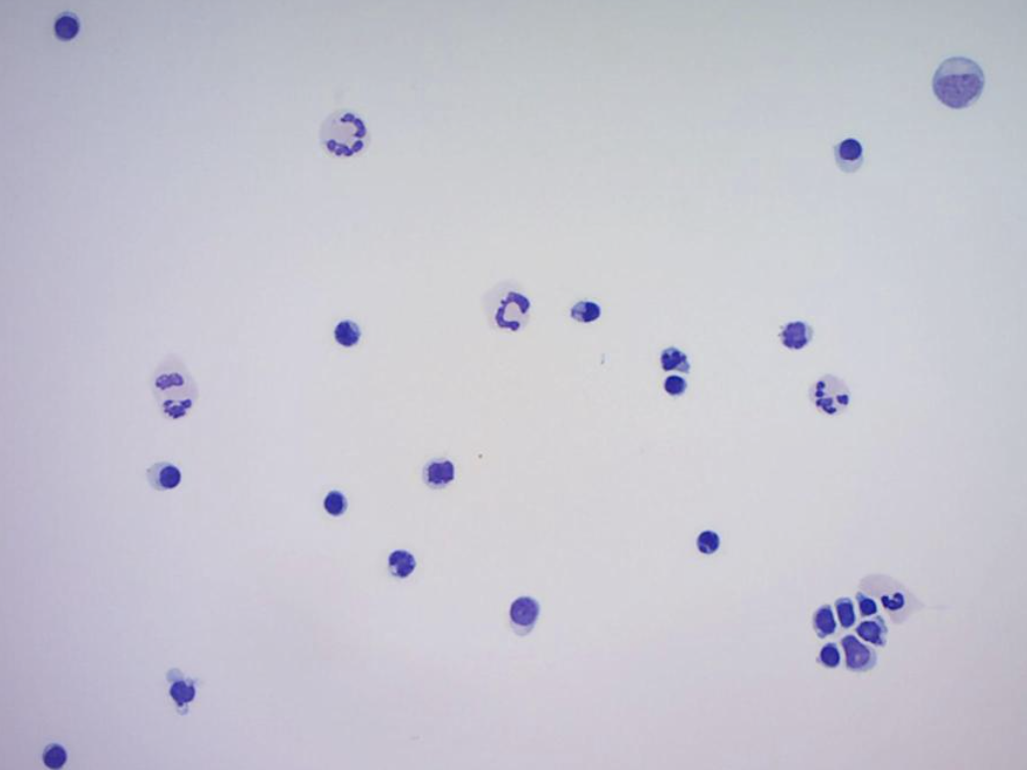

CSF and infectious disease testing results (see Figure 2 below):

- Rolly’s CSF cytology revealed a significant lymphocytic pleocytosis (430 nucleated cells/uL) and elevated protein (112.6 mg/dL).

- Her infectious testing was positive for toxoplasmosis on IgG (1:25) and IgM (1:50).

- She was negative for tickborne disease, cryptococcus, distemper (titer consistent with vaccination only), and Neospora.

Figure 2. Cytospin slide prepared from submitted cisternal CSF sample.

The CSF sample consisted of 65% lymphoid cells, 24% neutrophils and 11% large mononuclear cells. The lymphoid cell population observed were small to intermediate in size and well differentiated. No infectious organisms or cellular atypia were observed.

Clindamycin was recommended for 6 weeks total and a recheck neurological examination was scheduled for 2 weeks-post imaging or sooner if needed.

Rolly rechecked with Dr. Landry as she continued to neurologically decompensate despite oral clindamycin therapy. At this time oral prednisone was started (0.8 mg/kg every 24 hours) and Rolly neurologically improved within a few days of starting corticosteroids. Due to a neurological plateau on this dose, her dose was increased to an immunosuppressive one (1.8 mg/kg daily) and she continued to improve and walk on her own.

Rolly did well on immunosuppressive prednisone but repeatedly worsened as her prednisone was tapered. Dr. Landry initiated injectable cytosine arabinoside therapy on an outpatient basis, and Rolly as of the publication of this article is neurologically normal on 0.9 mg/kg prednisone daily and injectable cytosine arabinoside every 4 weeks. She is 6 months out from her original diagnosis, and she is slowly being tapered off her medications.

The long-term goal in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory CNS disease is to gradually taper them off prednisone over months, and then eventually off injectable cytosine arabinoside (or other immunosuppressant medications).

Rolly has a mildly hypermetric gait in her forelimbs but has an otherwise normal neurological examination as of the date of this publication. We are so proud of (and happy for) her as she continues to live a great quality of life with her family!

Clinically relevant facts:

- Immune-mediated meningoencephalomyelitis in dogs is a major differential for progressive neurological signs, especially in small to medium breeds.

- In this author’s experience immune-mediated meningoencephalomyelitis does not carry the grave prognosis seen in previously published literature, and many patients can be weaned off medications completely (or continue a good quality of life on the lowest effective dose of injectable +/- oral medications). There is a population of these patients who are refractory to treatment and do not respond despite aggressive immunosuppression, or who cannot be weaned off high doses of immunosuppressive medications.

- Cytosine arabinoside is an injectable anti-neoplastic medication that is used as an immunosuppressive agent in dogs. It is specific to the S phase of the cell cycle (DNA synthesis) and blocks cell progress from G1 phase to S phase. This drug has excellent penetration into the CNS making it a great option for inflammatory CNS disease as well as CNS lymphoma. This author’s starting protocol includes one subcutaneous injection of cytosine every 24 hours for two doses. This protocol is starts at an every 3-week interval and is then slowly pushed out as the oral prednisone is tapered. It is generally very well tolerated at the dose used for inflammatory CNS disease. Adverse side effects include myelosuppression, gastrointestinal upset, and liver toxicity at high doses.

- PVESC has an active out-patient cytosine arabinoside program for treatment of inflammatory CNS disease. This includes immune-medicated meningoencephalomyelitis, steroid-responsive meningitis arteritis (SRMA), and some other immune-mediated CNS diseases. Please do not hesitate to reach out to Dr. Landry or Dr. Eifler with any questions regarding this program (at specialty@pvesc.com).

Authored by: Amanda Landry, DVM, DACVIM, Neurology