Milo is an 11-year old MN Pomeranian who presented to our Neurology service for an acute onset of seizure-like episodes.

During the first episode, he began shaking, staring off, and holding up his right forelimb. He was then ataxic in all four limbs, quieter than normal for several minutes, and developed increased attention-seeking behavior with his owner for a few days.

On presentation to our Neurology service, Milo had an unremarkable neurological examination. Infectious testing revealed he was low positive for Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (@ 1:25) and Anaplasma (@1:100), and he was started on a 4-week course of doxycycline. When Milo had another episode despite being on antibiotics (this time with a component of hypermetria prior to holding up his right forelimb), a brain MRI was scheduled to further investigate the cause of his signs.

A brain MRI revealed a structurally unremarkable brain and atlantoaxial subluxation causing moderate extradural spinal cord compression. This unexpected finding of vertebral instability is suspected to be the cause of Milo’s episodes. A cervical splint was placed to stabilize the site prior to discharge, which will require weekly changing for 8 weeks.

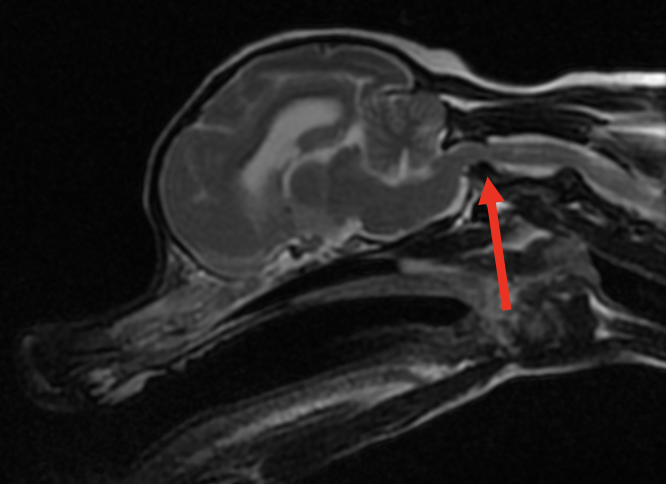

Figure 1. Sagittal T2- weighted image of the brain and high cervical spinal cord

The red arrow illustrates where the cranial aspect of C2 is dorsally displaced into the vertebral canal causing moderate extradural spinal cord compression and displacement. There is a loss of CSF and epidural fat signal at this site, consistent with spinal cord compression.

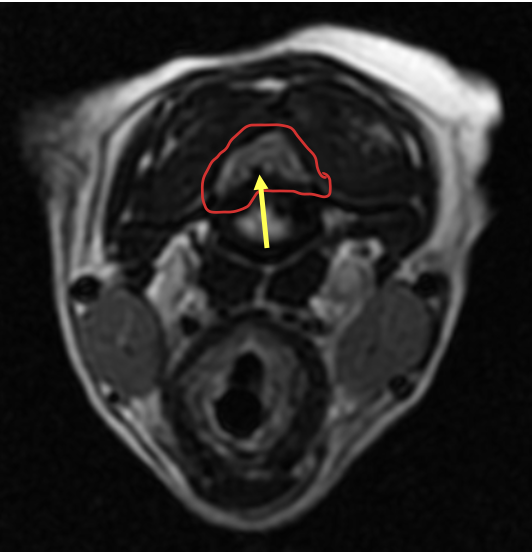

Figure 2. Axial T2- weighted image at the level of the cranial cervical spinal cord (red arrow in Figure 1)

The solid red line outlines the spinal cord which is moderately compressed from a protruding hypoplastic dens (yellow arrow).

Clinically relevant facts:

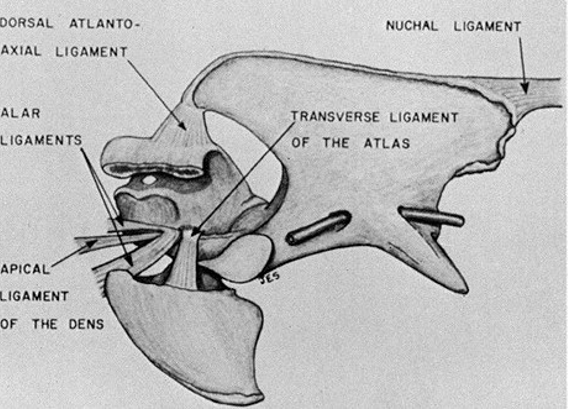

- Instead of an intervertebral disc, 5 ligaments help stabilize the joint between C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis). The apical ligament, 2 alar ligaments, and transverse ligament are associated with the odontoid process (dens). The dorsal atlantoaxial ligament attaches the spinous process of the axis with the dorsal arch of the atlas. See Figure 3 below.

- Congenital malformation of the dens (hypoplasia or aplasia) is common in toy breeds, which causes instability of the atlantoaxial joint and predisposes to subluxation. The most common presentation is dorsal subluxation of the axis (including the dens) causing ventral extradural compression of the cranial cervical spinal cord.

- While young toy breeds are the most commonly impacted patients, it has been reported in older animals (like Milo) and larger breed dogs.

- The degree of neurological dysfunction can vary greatly from neck pain alone to tetraplegia with respiratory compromise. When examining patients with suspected atlantoaxial instability extreme caution should be used when manipulating the neck, ESPECIALLY VENTROFLEXION, to avoid the peracute exacerbation of neurological signs and in some cases mortality.

- An MRI is recommended for diagnosis to view the integrity of the spinal cord and associated ligaments, however cautiously acquired cervical spine radiographs can also be used in some cases for a definitive diagnosis.

- Cervical bandaging with strict cage rest is recommended for a minimum of 8 weeks, along with analgesic medications and a corticosteroid taper. In some cases, surgical stabilization may be recommended (following MRI and CT imaging for planning).

- The prognosis for patients managed with splints who have mild to moderate neurological deficits has been reported as fair to good. Depending on the severity of clinical signs, the diagnosis of this condition should not automatically lead to humane euthanasia if owners are open to serial bandaging and rest. The current treatment of choice for the majority of patients with atlantoaxial subluxation is splinting rather than surgical intervention.

- Landry and Dr. Eifler are happy to consult on neurological cases by phone at 207-878-3121 or email specialty@pvesc.com.

Figure 3. Anatomy of the atlantoaxial joint and supporting ligaments.

Figure 4. Milo with his first cervical stabilization bandage.

Sources:

Dewey, Curtis W., and Ronaldo C. Da Costa. Practical Guide to Canine and Feline Neurology. Third edition. Wiley Blackwell, (2016): 361-62.

Gage, E D, and J E Smallwood. “Surgical repair of atlanto-axial subluxation in a dog.” Veterinary medicine, small animal clinician : VM, SAC vol. 65,6 (1970): 583-92.

Authored by: Amanda Landry, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)